How to Start a Startup - Y Combinator: The Vault

— business — 224 min read

Original Content

Table of Content

- Lecture 1 & 2 - Ideas, Products, Teams and Execution (Sam Altman, Dustin Moskovitz)

- Lecture 3 - Before the Startup (Paul Graham)

- Lecture 4 - Building Product, Talking to Users, and Growing (Adora Cheung)

- Lecture 5 - Competition is for Losers (Peter Thiel)

- Lecture 6 - Growth (Alex Schultz)

- Lecture 7 - How to Build Products Users Love (Kevin Hale)

- Lecture 8 - How to Get Started, Doing Things that Don't Scale, Press

- Lecture 9 - How to Raise Money (Marc Andreessen, Ron Conway, Parker Conrad)

- Lecture 10 - Culture (Brian Chesky, Alfred Lin)

- Lecture 11 - Hiring and Culture, Part 2 (Patrick and John Collison, Ben Silbermann)

- Lecture 12 - Building for the Enterprise (Aaron Levie)

- Lecture 13 - How to be a Great Founder (Reid Hoffman)

- Lecture 14 - How to Operate (Keith Rabois)

- Lecture 15 - How to Manage (Ben Horowitz)

- Lecture 16 - How to Run a User Interview (Emmett Shear)

- Lecture 17 - Lecture 17 - How to Design Hardware Products (Hosain Rahman)

- Lecture 18 - Legal and Accounting Basics for Startups (Kirsty Nathoo, Carolynn Levy)

- Lecture 19 - Sales and Marketing; How to Talk to Investors (Tyler Bosmeny; YC Partners)

- Lecture 20 - Later-stage Advice (Sam Altman)

Lecture 1 & 2 - Ideas, Products, Teams and Execution (Sam Altman, Dustin Moskovitz)

You may still fail. The outcome is something like idea x product x execution x team x luck, where luck is a random number between zero and ten thousand. Literally that much. But if you do really well in the four areas you can control, you have a good chance at at least some amount of success.

You should never start a startup just for the sake of doing so. There are much easier ways to become rich and everyone who starts a startup always says, always, that they couldn't have imagined how hard and painful it was going to be. You should only start a startup if you feel compelled by a particular problem and that you think starting a company is the best way to solve it. The specific passion should come first, and the startup second.

1. Idea

It's uncool to spend a lot of time thinking about the idea for a startup. You're just supposed to start, throw stuff at the wall, see what sticks, and not even spend any time thinking about if it will be valuable if it works. And pivots are supposed to be great, the more pivots the better.

Great execution is at least ten times as important and a hundred times harder than a great idea.

If you look at successful pivots, they almost always are a pivot into something the founders themselves wanted, not a random made up idea

It includes the size and the growth of the market, the growth strategy for the company, the defensibility strategy, and so on. When you're evaluating an idea, you need to think through all these things, not just the product. If it works out, you're going to be working on this for ten years so it's worth some real up front time to think through the up front value and the defensibility of the business.

Long-term thinking is so rare anywhere, but especially in startups. There is a huge advantage if you do it. Remember that the idea will expand and become more ambitious as you go. You certainly don't need to have everything figured out in your path to world domination, but you really want a nice kernel to start with. You want something that can develop in interesting ways.

The idea should come first and the startup should come second. Wait to start a startup until you come up with an idea you feel compelled to explore. This is also the way to choose between ideas. If you have several ideas, work on the one that you think about most often when you're not trying to think about work.

Another way of looking at this is that the best companies are almost always mission oriented. It's difficult to get the amount of focus that large companies need unless the company feels like it has an important mission. And it's usually really hard to get that without a great founding idea. A related advantage of mission oriented ideas is that you yourself will be dedicated to them. It takes years and years, usually a decade, to build a great startup. If you don't love and believe in what you're building, you're likely to give up at some point along the way. There's no way I know of to get through the pain of a startup without the belief that the mission really matters. A lot of founders, especially students, believe that their startups will only take two to three years and then after that they'll work on what they're really passionate about. That almost never works. Good startups usually take ten years. A third advantage of mission oriented companies is that people outside the company are more willing to help you. You'll get more support on a hard, important project, than a derivative one.

The hardest part about coming up with great ideas, is that the best ideas often look terrible at the beginning. If they sounded really good, there would be too many people working on them.

You can't get a monopoly right away. You have to find a small market in which you can get a monopoly and then quickly expand. This is why some great startup ideas look really bad at the beginning. "Today, only this small subset of users are going to use my product, but I'm going to get all of them, and in the future, almost everyone is going to use my product."

Here is the theme that is going to come up a lot: you need conviction in your own beliefs and a willingness to ignore others' naysaying. The hard part is that this is a very fine line. There's right on one side of it, and crazy on the other. But keep in mind that if you do come up with a great idea, most people are going to think it's bad. You should be happy about that, it means they won't compete with you. This also another reason why it's not really dangerous to tell people your idea. The truly good ideas don't sound like they're worth stealing.

You need a market that's going to be big in 10 years. Most investors are obsessed with the market size today, and they don't think at all about how the market is going to evolve. One of the big advantages of these sorts of markets - these smaller, rapidly growing markets - is that customers are usually pretty desperate for a solution, and they'll put up with an imperfect, but rapidly improving product.

In general, its best if you're building something that you yourself need. You'll understand it much better than if you have to understand it by talking to a customer to build the very first version. If you don't need it yourself, and you're building something someone else needs, realize that you're at a big disadvantage, and get very very close to your customers. Try to work in their office, if you can, and if not, talk to them multiple times a day.

Another somewhat counterintuitive thing about good startup ideas is that they're almost always very easy to explain and very easy to understand. If it takes more then a sentence to explain what you're doing, that's almost always a sign that its too complicated. It should be a clearly articulated vision with a small number of words.

2. Product

To build a really great company, you first have to turn a great idea into a great product. This is really hard, but its crucially important, and fortunately its pretty fun.

One of the most important tasks for a founder is to make sure that the company builds a great product. Until you build a great product, nothing else matters. When really successful startup founders tell the story of their early days its almost always sitting in front of the computer working on their product, or talking to their customers. That's pretty much all the time. They do very little else, and you should be very skeptical if your time allocation is much different. Most other problems that founders are trying to solve, raising money, getting more press, hiring, business development, et cetera, these are significantly easier when you have a great product. Its really important to take care of that first. Step one is to build something that users love.

Find a small group of users, and make them love what you're doing.

One way that you know when this is working, is that you'll get growth by word of mouth. If you get something people love, people will tell their friends about it. This works for consumer product and enterprise products as well. When people really love something, they'll tell their friends about it, and you'll see organic growth. If you don't have some early organic growth, then probably your product isn't really good enough yet.

If you try to build a growth machine before you have a product that some people really love, you're almost certainly going to waste your time. Breakout companies almost always have a product that's so good, it grows by word of mouth.

Over the long run, great product win. Don't worry about your competitors raising a lot of money, or what they might do in the future. They probably aren't very good anyway. Very few startups die from competition. Most die because they themselves fail to make something users love, they spend their time on other things.

Its much much easier to make a great product if you have something simple. Even if your eventual plans are super complex, and hopefully they are, you can almost always start with a smaller subset of the problem then you think is the smallest, and its hard to build a great product, so you want to start with as little surface area as possible. Another reason that simple's good is because it forces you to do one thing extremely well and you have to do that to make something that people love.

You need some users to help with the feedback cycle, but the way you should get those users is manually—you should go recruit them by hand. Don't do things like buy Google ads in the early days, to get initial users. You don't need very many, you just need ones that will give you feedback everyday, and eventually love your product.

Understand that group extremely well, get extremely close to them. Listen to them and you'll almost always find out that they're very willing to give you feedback. Even if you're building the product for yourself, listen to outside users, and they'll tell you how to make a product they'll pay for. Do whatever you need to make them love you, and make them know what you're doing. Because they'll also be the advocates that help you get your next users.

You want to build an engine in the company that transforms feedback from users into product decisions. Then get it back in from of the users and repeat. Ask them what the like and don't like, and watch them use it. Ask them what they'd pay for. Ask them if they'd be really bummed if your company went away. Ask them what would make them recommend the product to their friends, and ask them if they'd recommended it to any yet.

Great founders don't put anyone between themselves and their users. The founders of these companies do things like sales and customer support themselves in the early days. Its critical to get this loop embedded in the culture.

You really need to use metrics to keep yourself honest on this. It really is true that the company will build whatever the CEO decides to measure. Startups live on growth, its the indicator of a great product.

Why to Start a Startup

Its important to know what reason is yours, because some of them only make sense in certain contexts, some of them will actually, like, lead you astray.

So the 4 common reasons, just to enumerate them, are:

- it's glamorous

- you'll get to be the boss

- you'll have flexibility, especially over your schedule

- and you'll have the chance to have bigger impact and make more money then you might by joining a later stage company

It's glamorous

There's an ugly side to being an entrepreneur, and more importantly, what you're actually spending your time on is just a lot of hard work. Let's be real, if you start a company its going to be extremely hard.

Why is it so stressful?

- A lot of responsibility. People in any career have a fear of failure, its kind of just like a dominant part of the part of the psychology. But when you're an entrepreneur, you have fear of failure on behalf of yourself and all of the people who decided to follow you. So that's really stressful.

- You're always on call. If something comes up—maybe not always at 3 in the morning, but for some startups that's true—but if something important comes up, you're going to deal with it.

- You're much more committed. So if you're at a startup and it's very stressful and things are not going well, you're unhappy, you can just leave. For a founder, you can leave, but it's very uncool and pretty much a black eye for the rest of your career.

Ben Horowitz likes to say the number one role of a CEO is managing your own psychology, it's absolutely true, make sure you do it.

You'll be the boss

Another reason, especially if you're had another job at another company, you start to develop this narrative, like the people running this company are idiots, they're making all these decisions and spending all their time in these stupid ways, I'm gonna start a company and I'm going to do it better. I'm going to set all the rules.

"People have this vision of being the CEO of a company they started and being on top of the pyramid. Some people are motivated by that, but that’s not at all what it’s like.

What it’s really like: everyone else is your boss – all of your employees, customers, partners, users, media are your boss. I’ve never had more bosses and needed to account for more people today.

The life of most CEOs is reporting to everyone else, at least that’s what it feels like to me and most CEOs I know. If you want to exercise power and authority over people, join the military or go into politics. Don’t be an entrepreneur." - Phil Libin, CEO of Evernote

The most common thing I have to spend my time on and my energy on as a CEO is dealing with the problems that other people are bringing to me, the other priorities that people create, and it's usually in the form of a conflict. People want to go in different directions or customers want different things. And I might have my own opinions on that, but the game I'm playing is who do I disappoint the least and just trying to navigate all these difficult situations.

And even on a day to day basis, I might come in on Monday and have all these grand plans for how I'm going to improve the company. But if an important employee is threatening to quit, that's my number one priority. That's what I'm spending my time on.

Flexibility

"If you're going to be an entrepreneur, you will actually get some flex time to be honest. You'll be able to work any 24 hours a day you want!" - Phil Libin

You're a role model of the company, and this is super important. So if you're an employee at a company, you might have some good weeks and you might have some bad weeks, some weeks when you're low energy and you might want to take a couple days off. That's really bad if you're an entrepreneur. Your team will really signal off of what you're bringing to the table. So if you take your foot off the gas, so will they.

You're always working anyways. If you're really passionate about an idea, it's going to pull you towards it. If you're working with great investors, you're working with great partners, they're going to be working really hard, they're going to want you to be working really hard.

Money and Impact

If you joined Facebook a couple years into its existence you've already made around $200M, this is a huge number and even if you joined Facebook as employee number 1000, so you joined like 2009, you still make $20M, that's a giant number and that's how you should be benchmarking when you're thinking about what you might make as an entrepreneur.

So why might joining a late stage company actually might have a lot of impact, you get this force multiplier: they have an existing mass of user base, if it's Facebook it's a billion users, if it's Google it's a billion users, they have existing infrastructures you get to build on, that's also increasingly true for a new startup like AWS and all these awesome independent service providers, but you usually get some micro-proprietary technology and they maintain it for you, it's a pretty great place to start. And you get to work with a team, it'll help you leverage your ideas into something great.

So what's the best reason

"You can't not do it"

- Passion: you're so passionate about it that you have to do it and you're going to do it anyways. This is really important because you'll need that passion to get through all of those hard parts of being an entrepreneur.

- Aptitude: the world needs you to do it. You're actually well suited for this problem in some way. If this isn't true, it may be a sign that your time is better spent somewhere else.

3. Team

Cofounders

Cofounder relationships are among the most important in the entire company. Everyone says you have to watch out for tension brewing among cofounders and you have to address is immediately. And choosing a random random cofounder, or choosing someone you don't have a long history with, choosing someone you're not friends with, so when things are really going wrong, you have this sort of past history to bind you together, usually ends up in disaster. If you're not in college and you don't know a cofounder, the next best thing I think is to go work at an interesting company. If you work at Facebook or Google or something like that, it's almost as cofounder rich as Stanford.

You definitely need relentlessly resourceful cofounders. That model is James Bond. You need someone that behaves like James Bond more than you need someone that is an expert in some particular domain.

You want a tough and a calm cofounder. There are obvious things like smart, but everyone knows you want a smart cofounder, they don't prioritize things like tough and calm enough, especially if you feel like you yourself aren't, you need a cofounder who is.

Try not to hire

It sucks to have a lot of employees, and you should be proud of how few employees you have. Lots of employees ends up with things like a high burn rate, meaning you're losing a lot of money every month, complexity, slow decision making, the list goes on and it's nothing good. You want to be proud of how much you can get done with a small numbers of employees.

At the beginning, you should only hire when you desperately need to. Later, you should learn to hire fast and scale up the company, but in the early days the goal should be not to hire. And one of the reasons this is so bad, is that the cost of getting an early hire wrong is really high. These hires really matter, these people are what go on to define your company, and so you need people that believe in it almost as much as you do.

One of the remarkable observations about Airbnb is that if you talk to any of the first forty or so employees, they all feel like they were a part of the founding of the company. But by having an extremely high bar, by hiring slowly ensures that everyone believes in the mission, you can get that.

Get the best people

When you're in product mode that should be your number one priority. And when you're in fundraising mode, fundraising is your number one priority.

To get the very best people, they have a lot of great options and so it can easily take a year to recruit someone. It's this long process and so you have to convince them that your mission is the most important of anything that they're looking at. This is another case of why it's really important to get the product right before looking at anything else. The best people know that they should join a rocketship.

If you compromise and hire someone mediocre you will always regret it. Mediocre people at huge companies will cause some problems, but it won't kill the company. A single mediocre hire within the first five will often in fact kill a startup. "Mediocre engineers do not build great companies"

The best source for hiring by far is people that you already know and people that other employees in the company already know.

Experience matters for some roles and not for others. When you're hiring someone that is going to run a large part of your organization experience probably matters a lot. For most of the early hires that you make at a startup, experience probably doesn't matter that much and you should go for aptitude and belief in what you’re doing. Most of the best hires that I've made in my entire life have never done that thing before. So it's really worth thinking, is this a role where I care about experience or not. And you'll often find to don’t, especially in the early days.

There are 3 things I look for in a hire:

- Are they smart?

- Do they get things done?

- Do I want to spend a lot of time around them?

And if I get an answer, if I can say yes to all three of these, I never regret it, it's almost always worked out. You can learn a lot about all three of these things in an interview but the very best way is working together, so ideally someone you've worked together with in the past and in that case you probably don't even need an interview.

You should ask specifically about projects that someone worked on in the past. You'll learn a lot more than you will with brainteasers. You want to call some people that these people have worked with in the past. And when you do, you don't just want to ask, How was so-and-so, you really want to dig in. Is this person in the top five percent of people you've ever worked with? What specifically did they do? Would you hire them again? Why aren't you trying to hire them again? You really have to press on these reference calls.

- Communication is so important in an early startup. If someone is difficult to talk to, if someone cannot communicate clearly, it's a real problem in terms of their likelihood to work out.

- Manically determined: you want people that are just going to get it done.

- Would feel comfortable reporting to them, if the roles were reversed. You don't have to be friends with everybody, but you should at least enjoy working with them. And if you don't have that, you should at least deeply respect them.

You should aim to give about ten percent of the company to the first ten employees. They have to earn it over 4 years anyway, and if they're successful, they're going to contribute way more than that. They're going to increase the value of the company way more than that, and if they don't then they won't be around anyway.

For whatever reason founders are usually very stingy with equity to employees and very generous with equity for investors. I think this is totally backwards. Employees will only add more value over time. Investors will usually write the check and then, despite a lot of promises, don't usually do that much. Sometimes they do, but your employees are really the ones that build the company over years and years.

You've hired the best - now keep them around!

You have to make sure your employees are happy and feel valued. This is one of the reasons that equity grants are so important. People in the excitement of joining a startup don't think about it much, but as they come in day after day, year after year, if they feel they have been treated unfairly that will really start to grate on them and resentment will build.

Learning just a little bit of management skills, which first-time CEOs are usually terrible at, goes a long way. One of the speakers at YC this summer, who is now extremely successful, struggled early on and had his team turn over a few times. Someone asked him what his biggest struggle was and he said, turns out you shouldn't tell your employees they're fucking up every day unless you want them all to leave because they will.

As a founder, this is a very natural instinct. You think you can do everything the best and it’s easy to tell people when they’re not doing it well. So learning just a little bit here will prevent this massive team churn. It also doesn't come naturally to most founders to really praise their team. It took me a little while to learn this too. You have to let your team take credit for all the good stuff that happens, and you take responsibility for the bad stuff.

Dan Pink talks about these three things that motivate people to do great work: autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

People that are really smart and that can learn new things can almost always find a role in the company as time goes on. You may have to move them into something else, something other than where they started. Really good people that can almost find some great place in the company, I have not seen that be a problem too often.

Fire fast

Every first time founder waits too long, everyone hopes that an employee will turn around. But the right answer is to fire fast when it's not working. It's better for the company, it's also better for the employee. But it's so painful and so awful, that everyone gets it wrong the first few times.

You also wanna fire people who are creating office politics, and who are persistently negative. The rest of the company is always aware of employees doing things like this, and it's just this huge drag - it's completely toxic to the company.

If someone is getting every decision wrong, that's when you need to act, and at that point it'll be painfully aware to everyone. It's not a case of a few screw-ups, it's a case where every time someone does something, you would have done the opposite yourself. You don't get to make their decisions but you do get to choose the decision-makers. And, if someone's doing everything wrong, just like a consistent thing over like a period of many weeks or a month, you'll be aware of it.

If you have to choose between hiring a sub-optimal employee and losing your customers to a competitor, what do you do? If it's going to be one of the first five employees at a company I would lose those customers. The damage that it does to the company- it's better to lose some customers than to kill the company.

4. Execution

Execution for most founders is not the most fun part of running the company, but it is the most critical. Many cofounders think they're just signing up to this beautiful idea and then they're going to go be on magazine covers and go to parties. But really what it’s about more than anything else, what being a cofounder really means, is signing up for this years long grind on execution and you can’t outsource this.

The way to have a company that executes well is you have to execute well yourself. Every thing at a startup gets modeled after the founders. Whatever the founders do becomes the culture. So if you want a culture where people work hard, pay attention to detail, manage the customers, are frugal, you have to do it yourself. There is no other way. You cannot hire a COO to do that while you go off to conferences. The company just needs to see you as this maniacal execution machine.

There’s at least a hundred times more people with great ideas than people who are willing to put in the effort to execute them well. Ideas by themselves are not worth anything, only executing well is what adds and creates value.

The CEO has 5 jobs: set the vision, raise money, evangelize, hire and manage, make sure the entire company executes.

Focus

Execution gets divided into two key questions: can you figure out what to do and can you get it done.

One of the hardest parts about being a founder is that there are a hundred important things competing for your attention every day. And you have to identify the right two or three, work on those, and then ignore, delegate, or defer the rest.

Founders get excited about starting new things. Unfortunately the trick to great execution is to say no a lot.

Most startups are nowhere near focused enough. They work really hard-maybe-but they don’t work really hard at the right things, so they'll still fail. One of the great and terrible things about starting a start up is that you get no credit for trying. You only get points when you make something the market wants. So if you work really hard on the wrong things, no one will care.

You can't be focused without good communication. Even if you have only four or five people at a company, a small communication breakdown is enough for people to be working on slightly different things.

Growth and momentum are what a startup lives on and you always have to focus on maintaining these. You should always know how you're doing against your metrics, you should have a weekly review meeting every week. So you want to have the right metrics and you want to be focused on growing those metrics and having momentum. Don't let the company get distracted or excited about other things.

Intensity

Startups only work at a fairly intense level. A friend of mine says the secret to start up success is extreme focus and extreme dedication.

Startups are not the best choice for work life balance and that's sort of just the sad reality. There's a lot of great things about a startup, but this is not one of them. Startups are all-consuming in a way that is generally difficult to explain. You basically need to be willing to outwork your competitors.

The good news here is that a small amount of extra work on the right thing makes a huge difference. Just outworking their competitors by a little bit was what made them successful.

It's easy to move fast or be obsessed with quality, but the trick is to do both at a startup. You need to have a culture where the company has really high standards for everything everyone does, but you still move quickly.

Indecisiveness is a startup killer. Mediocre founders spend a lot of time talking about grand plans, but they never make a decision. They're talking about you know I could do this thing, or I could do that other thing, and they're going back and forth and they never act. And what you actually need is this bias towards action. The best founders work on things that seem small but they move really quickly. But they get things done really quickly. Every time you talk to the best founders they've gotten new things done.

Speed is this huge premium. The best founders usually respond to e-mail the most quickly, make decisions most quickly, they're generally quick in all of these ways. And they had this do what ever it takes attitude.

Momentum

Momentum and growth are the lifeblood of startups. This is probably in the top three secrets of executing well. You want a company to be winning all the time. If you ever take your foot off the gas pedal, things will spiral out of control, snowball downwards.

A winning team feels good and keeps winning. A team that hasn’t won in a while gets demotivated and keeps losing. So always keep momentum, it’s this prime directive for managing a startup. If I can only tell founders one thing about how to run a company, it would be this.

It’s hard to figure out a growth engine because most companies grow in new ways, but there’s this thing: if you build a good product it will grow. So getting this product right at the beginning is the best way not to lose momentum later.

When there’s disagreement among the team about what to do, then you ask your users and you do whatever your users tell you. And you have to remind people: “hey, stuff’s not working right now we don’t actually hate each other, we just need to get back on track and everything will work.” If you just call it out, if you just acknowledge that, you’ll find that things get way better.

A good way to keep momentum is to establish an operating rhythm at the company early. Where you ship product and launch new features on a regular basis. Where you’re reviewing metrics every week with the entire company. This is actually one of the best things your board can do for you. Boards add value to business strategy only rarely. But very frequently you can use them as a forcing function to get the company to care about metrics and milestones.

Don’t worry about a competitor at all, until they’re actually beating you with a real, shipped product. Press releases are easier to write than code, and that is still easier than making a great product. So remind your company of this, and this is sort of a founder’s role, is not to let the company get down because of the competitors in the press.

“The competitor to be feared is one who never bothers about you at all, but goes on making his own business better all the time.” - Henry Ford

Lecture 3 - Before the Startup (Paul Graham)

Advice that does not surprise you

You don't need people to give you advice that does not surprise you. If founders' existing intuition gave them the right answers, they would not need us. You can trust your instincts about people. Work with people you would generally like and respect and that you have known long enough to be sure about because there are a lot of people who are really good at seeming likable for a while.

Mechanics of starting a startup

It's not merely unnecessary for people to learn in detail about the mechanics of starting a startup, but possibly somewhat dangerous because another characteristic mistake of young founders starting startups is to go through the motions of starting a startup. They always want to know, what are the tricks for convincing investors? And we have to tell them the best way to convince investors is to start a startup that is actually doing well, meaning growing fast, and then simply tell investors so.

Gaming the system stops working

Starting a startup is where gaming the system stops working. Users are like sharks, sharks are too stupid to fool, you can't wave a red flag and fool it, it's like meat or no meat. You have to have what people want and you only prosper to the extent that you do. The dangerous thing is, faking does work to some extent with investors. If you’re really good at knowing what you’re talking about, you can fool investors, for one, maybe two rounds of funding.

So, stop looking for the trick.

Startups are all consuming

If you start a startup, it will take over your life to a degree that you cannot imagine and if it succeeds it will take over your life for a long time; for several years, at the very least, maybe a decade, maybe the rest of your working life. Every day shit happens within the Google empire that only the emperor can deal with and he, as the emperor, has to deal with it. If he goes on vacation for even a week, a whole backlog of shit accumulates, and he has to bear this, uncomplaining, because: number one, as the company’s daddy, he cannot show fear or weakness; and number two, if you’re a billionaire, you get zero, actually less than zero sympathy, if you complain about having a difficult life.

Starting a successful startup is similar to having kids; it's like a button you press and it changes your life irrevocably. While it's honestly the best thing—having kids—if you take away one thing from this lecture, remember this: There are a lot of things that are easier to do before you have kids than after, many of which will make you a better parent when you do have kids.

Should you start a startup at any age?

You can't tell. Meaning starting a startup will change you a lot if it works out. So what you’re trying to estimate is not just what you are, but what you could become. The hard part and the most important part was predicting how tough and ambitious they would become.

If you are absolutely terrified of starting a startup you probably shouldn’t do it. Unless you are one of those people who gets off on doing things you're afraid of. Otherwise if you are merely unsure of whether you are going to be able to do it, the only way to find out is to try.

So if you want to start a startup one day, what do you do now in college? There are only two things you need initially, an idea and cofounders.

The way to get start up ideas is not to try to think of startup ideas

If you make a conscious effort to try to think of startup ideas, you will think of ideas that are not only bad but bad and plausible sounding. Meaning you and everybody else will be fooled by them. You'll waste a lot of time before realizing they're no good.

The way to come up with good startup ideas is to take a step back. Instead of trying to make a conscious effort to think of startup ideas, turn your brain into the type that has startup ideas unconsciously. In fact, so unconsciously that you don't even realize at first that they're startup ideas.

How do you turn your mind into the kind that has startup ideas unconsciously?

- learn about a lot of things that matter.

- work on problems that interest you.

- with people you like and or respect.

QnA

The component of entrepreneurship that really matters is domain expertise. Larry Page is Larry Page because he was an expert on search and the way he became an expert on search was because he was genuinely interested and not because of some ulterior motive. At its best starting a startup is merely a ulterior motive for curiosity and you’ll do it best if you introduce the ulterior motive at the end of the process. So here is ultimate advice for young would be startup founders reduced to two words: just learn.

Q: Do you see any value in business school for people who want to pursue entrepreneurship? A: Honestly the best way to learn on how to start a startup is just to just try to start it. You may not be successful but you will learn faster if you just do it.

Q: Management is a problem only if you are successful. What about those first two or three people? A: Ideally you are successful before you even hire two or three people. Ideally you don't even have two or three people for quite awhile. When you do the first hires in a startup they are almost like founders. They should be motivated by the same things, they can’t be people you have to manage. As a general rule you want people who are self motivated early on they should just be like founders.

Q: What are your reoccurring systems in your work and personal life that make you efficient? A: If you work on things you like, you don't have to force yourself to be efficient.

Q: If you hire people you like, you might get a monoculture and how do you deal with the blind spots that arise? A: Starting a startup is where many things will be going wrong. You can't expect it to be perfect. The advantage is of hiring people you know and like are far greater than the small disadvantage of having some monoculture. You look at it empirically, at all the most successful startups, someone just hires all their pals out of college.

Lecture 4 - Building Product, Talking to Users, and Growing (Adora Cheung)

problem

- what is it solving? describe it in 1 sentence

- how does it relate to you? am i really passionate about the problem

- verify others have it

where to start?

- learn a lot, become an expert so people trust you

- identify customer segments

- storyboard ideal user experience, how people find out about you

what is v1?

- minimum viable product: smallest feature set to solve the problem

- simple product positioning: one-liner to describe functional benefits of what you do

first few users

- sphere of influence

- local & online communities

- niche influencers

- cold calls + emails

- press

customer feedback

- support email & phone number

- surveys, interviews

- quantitative: retention, ratings, Net Promoter Score

- qualitative: ask why why why

- beware of honesty curve: be wary of feedback from people you know and is the product is free or paid, the most honest feedback is from random paid users because they want to know if their money is worth it

v1 feature creep

- build fast, but optimise for now

- manual before automation: do it manually until it can be automated

- temporary brokeness > permanent paralysis: perfection is irrelevant in this stage, do not worry about the edge cases, over time they will build up, you'll want to build for that

- beware of frankenstein: don't build all features users ask for and make them happier, understand why they are asking, usually what they suggest is not the best idea

s is for stealth, and stupid

- someone will steal your idea

- there is a first-mover advantage

- just launch it already

ready for a lot of users?

- learn on channel at a time

- iterate working channels

- revisit failed channels

types of growth

- sticky: get existing users to come back and pay you more

- viral: when people talk about you

- paid: use money

- key = sustainability, good return on investment

sticky growth

- good experience wins

- Customer's Lifetime Value CLV + retention cohort analysis important

- repeat users buy more and more

viral growth

- WOW experience + good referral programs

- customer touch points: where can people refer other people

- program mechanics

- referral conversion flow

paid growth

- online ads: Search Engine Marketing SEM, Social Media Marketing SMM, etc.

- offline ads: flyers, newspaper ads, press releases, etc.

- b2b sales

- simple: Customer Lifetime Value CLV > Customer Acquisition Cost CAC

- advanced: CLV > CAC by segment

- key: payback time + sustainability

the art of pivoting: when to move on?

- bad growth

- bad retention

- bad economics

- key: have a growth plan when you start out: what's the optimistic but realistic way to grow this business?

Lecture 5 - Competition is for Losers (Peter Thiel)

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future - Peter Thiel, Blake Masters

Lecture 6 - Growth (Alex Schultz)

When you want to start a startup also see how big the market could be

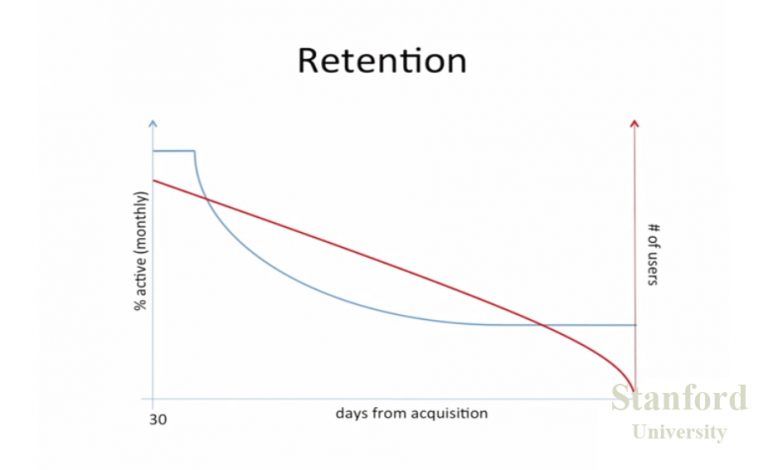

Retention Curve

Retention is the single most important thing for growth

This curve, ‘percent monthly active’ versus ‘number of days from acquisition’, if you end up with a retention curve that is asymptotic to a line parallel to the X-axis, you have a viable business and you have product market fit for some subset of market

If it doesn’t flatten out, don’t go into growth tactics, don’t do virality, don’t hire a growth hacker. Focus on getting product market fit, because in the end, as Sam said in the beginning of this course: idea, product, team, execution. If you don’t have a great product, there’s no point in executing more on growing it because it won’t grow. Number one problem I’ve seen, inside Facebook for new products, number one problem I’ve seen for startups, is they don’t actually have product market fit, when they think they do.

Different verticals need different terminal retention rates for them to have successful businesses.

- If you’re on ecommerce and you’re retaining on a monthly active basis, like 20 to 30% of your users, you’re going to do very well.

- If you’re on social media, and the first batch of people signing up to your product are not like, 80% retained, you’re not going to have a massive social media site.

What you need to do is have the tools to think, ‘who out there is comparable’ and how you can look at it and say, ‘am I anywhere close to what real success looks like in this vertical?’

Retention is the single most important thing for growth and retention comes from having a great idea and a great product to back up that idea, and great product market fit. The way we look at, whether a product has great retention or not, is whether or not the users who install it, actually stay on it long-term, when you normalize on a cohort basis, and I think that’s a really good methodology for looking at your product and say ‘okay the first 100, the first 1,000, the first 10,000 people I get on this, will they be retained in the long-run?

The North Star

Startups should not have growth teams. The whole company should be the growth team. The CEO should be the head of growth. You need someone to set a North star for you about where the company wants to go, and that person needs to be the person leading the company.

- Mark put out monthly active users, as the number both internally he held everyone to, and said we need everyone on Facebook, but that means everyone active on Facebook, not everyone signed up on Facebook, so monthly active people was the number internally, and it was also the number he published externally.

- If you’re a messaging application, sends is probably the single most important number. If people use you once a day, maybe that’s great, but you’re not really their primary messaging mechanism, so Jan published the sends number.

- Inside Airbnb, they talk about ‘nights booked’ and also published that in all of the infographics you see in side TechCrunch. They always benchmark themselves against how many nights booked they have compared to the largest hotel chains in the world.

- For eBay, it was gross merchandise volume. How much stuff did people actually buy through eBay? Everyone externally tends to judge eBay based on revenue. It actually has 10 times Gross Merchandise Volume going through the site.

When you are operating for growth it is critical that you have that North star, and you define as a leader. The second you have more than one person working on something, you cannot control what everyone else is doing. I promise you, having now hit 100 people I’m managing, I have no control. It’s all influence

The Magic Moment

- Facebook the magic moment, is that moment when you see your friend’s face, and everything we do on growth.

- Linkedin, Twitter, Whatsapp sign up: the number one thing all these services look to do, is show you the people you want to follow, connect to, send messages to, as quickly as possible, because in this vertical, this is what matters.

- eBay: Like when you see that collectible that you are missing, that is the real magic moment on eBay. When you’re listing your house, that first time you get paid, is your magic moment or when you list an item on eBay, the first time you get paid, is your magic moment.

- Airbnb: you find that first listing, that cool house you can stay in, and when you go through the door, that’s a magic moment.

Think about what the magic moment is for your product, and get people connected to it as fast as possible, because then you can move up where that blue line has asymptotic, and you can go from 60% retention to 70% retention easily if you can connect people with what makes them stick on your site.

Marginal User (Power User)

‘Oh, I’m getting too many notifications, I think that’s what we have to optimize for on notifications.’ Okay, are your power users leaving your site because they’re getting too many notifications? No. Then why would you optimize that? They’re probably grown-ups and they can use filters.

What you need to focus on is the marginal user. The one person who doesn’t get a notification in a given day, month, or year. Building an awesome product is all about think about the power user, right? Building an incredible product is definitely optimizing it for the people who use your product the most, but when it comes to driving growth, people who are already using your product are not the ones you have to worry about.

The resurrected and churned numbers for pretty much every product I’ve ever seen dominate the new user account once you reach a sensible point of growth a few years in. And all those users who are churning and resurrecting, had low friend counts, and didn’t find their friends so weren’t connected to the great stuff that was going on on Facebook. So the number one thing we needed to focus on, was getting them to those 10 friends, or whatever number of friends they needed.

Summary

What is that 1 metric, where if everyone in your company is thinking about it and driving their product towards that metric and their actions towards moving that metric up, you know in the long-run your company will be successful.

A lot of things end up being correlated. Pick the one that fits with you and know that you’re going to stick with for a long time. Just have a North Star, and know the magic moment that you know when a user experiences that, they will deliver on that metric for you on the North Star, and then think about the marginal user, don’t think about yourself. Those are, I think, the most important points when operating for growth.

Tactics

Internationalization

- Facebook started out as college-only, so every college that it was launched in was knocking down a barrier.

- When Facebook expanded beyond colleges to high schools, but that was a company-shaking moment where people questioned whether or not Facebook would survive.

- Then after, expanding from high schools to everyone, it was a shocking moment; that’s what spurred the growth up to 50 million, and then we hit a brick wall. Everyone had tapped out between 50 and 100 million users, and we were worried that it wasn’t possible. That was the point at which the growth team got set up. The 2 things we did, 1. We focused on that 10 friends in 14 days 2. Getting users to the magic moment.

- Even though we were late in internationalization we took the time to build it in a scalable way; we moved slow to move fast. What we did was draw all the strings on the site in FBT, which is our translation extraction script and then, we created the community translation platform. We got French translated in 12 hours. We managed to get, to this day, 104 languages translated by Facebook for Facebook, 70 of those are translated by the community. We took the time to build something, that would enable us to scale.

Virality

Books: "Viral Loop" & "Ogilvy on Advertising"

Fundamental

- Payload: how many people can you hit with any given viral blast

- Conversion rate

- Frequency

Hotmail is the canonical example of brilliant viral marketing. Back when Hotmail launched, there were a bunch of mail companies that had been funded and were throwing huge amounts of money at traditional advertising. Back in that time, people couldn’t get free email clients; they had to be tied to their ISP. Hotmail and a couple other companies launched, and their clients were available wherever you went. You could log-in via library internet or school internet, and be able to get access to that. It was a really big value proposition for anyone who wanted to access it. Most of the companies went out there and did big TV campaigns, billboard campaigns, or newspaper campaigns; however, the Hotmail team didn’t have much funding as they did, so they had to scramble around to figure out how to do it. What they did was add that little link at the bottom of every email that said, ‘Sent from Hotmail. Get your free email here.’ Hotmail ended up being extremely viral because it had high frequency and high conversion rates:

- Payload was low: you email one person at a time, you’re not necessarily going to have a big payload.

- Frequency is high: you’re emailing the same people over and over, which means you’re going to hit those people once, twice, three times a day and really bring up the impressions

- Conversion rate was also really high: people didn’t like being tied to their ISP email.

Paypal is interesting because there are two sides to it, the buyer and the seller side. The other thing that is interesting is that its mechanism for viral growth is eBay. So you can use a lot of things for virality that may not look necessarily obviously viral. They were able to go viral because their conversion rate was high on the buyer and the seller side, not because their payload and frequency was high:

- Payload was low

- Frequency was low

- Conversation rate is super high: you send money to seller, and give free money to buyer for signing up

Facebook was purely viral via word of mouth. The interesting thing about Paypal and Hotmail, is to use them, the first person has to send an email to a person who wasn’t on the service. With Facebook, there is no native way to contact people who aren’t on the service. Everyone thinks that Facebook is a viral marketing success, but that’s actually not how it grew. It was word of mouth virality because it was an awesome product you wanted to tell your friends about.

Frequency and conversation rate are related. The more times you hit someone with the same Facebook ad, the less they’ll click. That’s why we have to, like creative exhaustion, rotate creatives on Facebook. Same with banner ads and news feed stories. The same is true with these emails. So if you send the same email to people over and over again with an invite, you will get a lower conversion rate. ‘The more you hit someone with the same message, the less they convert’ is fundamental across every online marketing channel.

The K Factor

So with virality, you get someone to contact import. Then the question is, how many of those people do you get to send imports? Then, to how many people? Then, how many click? How many sign up? And then how many of those import. So essentially you want people to sign up to your site to import their contacts. You want to then get them to send an invite to all of those contacts - ideally all of those contacts, not just some of them. Then you want a percentage of those to click and sign up. If you multiply all the percentages/numbers in every point in between the steps, this is essentially how you get to the point of ‘What is the K factor?’ For example:

- people get an invite per person who imports: 100

- 10% click: 10

- 50% sign up: 5

- only 10 to 20% import: 0.5 - 1

- K factor: 0.5 - 1.0 -> and you’re not going to be viral.

The real important thing is still to think about retention, not so much virality, and only do this after you have a large number of people retained on your product per person who signs up.

SEO: Search Engine Optimization

- Keyword research: Supply (what do people search for that’s related to your site), Demand (how many people search for it), Value (how valuable is it for you)

- Links: the single most important thing is to get valuable links from high authority websites for you to rank in Google. Then you need to distribute that love inside your site by internally linking effectively

- XML Sitemaps

ESPN: Email, SMS, Push Notification

Email is dead for people under 25 in my opinion. Young people don’t use email. They use WhatsApp, SMS, SnapChat, Facebook; they don’t use email. If you’re targeting an older audience, email is still pretty successful. Email still works for distribution, but realistically, email is not great for teenagers - even people at universities.

Email, SMS, and Push Notifications all behave the same way. They all have questions of deliverability. If someone gives you a hard bounce, retry once or twice and then stop trying because if you are someone who abuses people’s inboxes, the email companies spam folder you, and it’s very hard to get out. If you get caught in a spam house link, or anything like that, it’s very hard to get out. It’s really important with email that you are a high class citizen, and that you do good work with email because you want to have deliverability for the long run.

You actually spam your power users and give them notifications they don’t care about, making it really hard for them to opt out. Well, they start blocking you, and you can never push them once they’ve opted out of your Push Notifications. And it’s very hard to prompt them to turn them on once they’ve turned them off. Email, SMS, and Push Notifications is, you have to get them delivered. Beyond that, it’s a question of open rate, click rate.

The most effective email you can do is notifications. So what are you sending? What should you be notifying people of? This is a great place where we’re in the wrong mindset. As a Facebook user, I don’t want Facebook to email me about every ‘like’ I receive, because I receive a lot of them since I have a lot of Facebook friends. But as a new Facebook user, that first ‘like’ you receive is a magic moment

- what notifications should we be sending

- how can you create great triggered marketing campaigns

- make sure you have deliverability

Lecture 7 - How to Build Products Users Love (Kevin Hale)

Growth is the interaction between two concepts or variables: conversion rate and churn. The gap between those two things pretty much indicates how fast you're going to grow.

The best way to get to $1 billion is to focus on the values that help you get that first dollar to acquire that first user. If you get that right, everything else will take care of itself.

The average successful company has raised $25.3 million, and sold for $196.8 million, for investor profits of 676%. (TechCrunch 2012)

"What's interesting about startups in terms of us wanting to create things that people love, is that love and unconditional feelings, are difficult things for us to do in real life. In startups, we have to do it at scale." So we decided to start off by asking, “How do relationships work in the real world and how can we apply them to the way we run our business and build our product that way?” 2 metaphors:

- acquiring new users: as if we are trying to date them

- existing users: as if they are a successful marriage.

First Impressions

First impressions are important for the start of any relationship because it's the one we tell over and over again, right? There’s something special about how we regard that origin story.

So something about first-time interactions means that the threshold was so much lower in terms of pass fail. So in software and for most products in Internet software that we use, first impressions are pretty obvious and there are things you see a lot of companies pay attention to in terms of what they send their marketing people to work on. All of those are opportunities to seduce

- the first email you ever get

- what happens when you got your first login

- the links, the advertisements, the very first time you interacted with customer support.

- homepage, landing pages, plans, pricing, login, signup

- first email, account creation, starting interface, first support ticket

"is this a quality item?"

- taken for granted for quality "atarimae hinshitsu" (e.g. a brush will paint)

- enchanting/aesthetic quality "miryokuteki hunshisu" (e.g. a brush will paint in a way that is pleasing to the viewer)

Long Term Relationship

Everyone fights:

- money: cost/billing

- kids: users' clients

- sex: performance

- time: roadmap

- others: others

As we were building up the company, we realized that there's a big problem with how everyone starts up their company or builds up their engineering teams. There's a broken feedback loop there. People are divorced from the consequences of their actions. This is a result from the natural evolution of how most companies get founded, especially by technical cofounders.

- Before launch, it is a time of bliss, Nirvana, and opportunity. Nothing that you do is wrong. By your hand, which you feel is like God, every line you write and every code you write feels perfect; it's genius to you.

- The thing that happens is after launch, reality sets in, and all these other tasks come in to play; things that we have to deal with. Now what technical cofounders want to do is get back to that initial state, so what we often see is the company starts siloing off these other things that makes a startup company real, and have other people do them. In our minds these other tasks are inferior, and we have other people in the company do them.

Support Driven Development (SDD): It's a way of creating high-quality software, but it's super simple: creators = supporters. All you have to do is make everyone do customer support. What you end up having is you fix the feedback. The people who built the software are the ones supporting it, and you get all these nice benefits as a result.

Developers & Designers Give the Best Support

The reason that we often break up with one another is due to four major causes.

- criticism: "you never think about us"

- contempt: somebody is purposely trying to insult another person

- defensiveness

- stonewalling: shutting down. The act of not even getting back to the users is probably some of the biggest causes of churn in the early stages of startups

Developers & Designers Create Better Software

There's a direct correlation to how much time we spend directly exposed to users and how good our designs get

- direct exposure: interact in somewhat real time

- minimum every 6 weeks

- for at least 2 hours

2 ways to fix knowledge gap:

- get user to increase their knowledge

- get user to decrease the amount of knowledge that's needed to use the application

Often times as engineers or people who build and work on these products we think let's add new features. New features only means let's increase the knowledge gap. Possible solution is to help the customers to help themselves

- FAQ

- tooltips

- help link that leads to specific page

- redesign documentation over and over again, A/B test it constantly

There's almost no difference in growth, however the latter is actually much easier and cheaper to do:

- +1% conversion

- -1% churn

"I care about you"

In products and companies is by doing things like creating a blog or making a newsletter. The thing is we look at these rates and basically it was such a small percentage of our active users, most of them had no idea about the awesome things that we were doing for them

- blog, newsletter

- user feature request board

- handwritten thank you cards with some stickers

- "since you've been gone" feature: what changes since the last login. "Dude I love that 'Since you've been gone' thing. Even though I pay the same amount every single month, you guys are doing something for me almost every week. It's totally awesome; it makes me feel like I'm getting maximum value."

Market Dominance

- Best Price: focus on logistics

- Best Product: focus on R&D

- Best Overall Solution: be customer intimate

"Best Overall Solution" is the only one that everyone can do at any stage of their company. It requires almost no money to get started with it. It usually just requires a little bit of humility and some manners. And as a result, you can achieve the success of any other people in of your market.

Q: So what do you do when you have a product with many different types of users? How do you build one product that all these users love? A: When you want to shoot for something witty, you have to get functionality right. So like the Japanese quality. If you don't have atarimae, don't try to do anything witty, because it'll backfire. So hands down our number one focus is to make everything as easy to use as possible; everything else was just polish.

Lecture 8 - How to Get Started, Doing Things that Don't Scale, Press

Just launched because at the beginning it's all about testing the idea, trying to get this thing off the ground, and figuring out if this was something people even wanted. And it's okay to hack things together at the beginning.

It also allows you to become an expert in your business, like driving helped us understand how the whole delivery process worked. We used that as an opportunity to talk to our customers, talk to restaurants. We would manually email every single new customer at the end of every night asking how their first delivery went, and how they heard about us. We would personalize all these emails

At the beginning it's all about getting the thing off the ground, and trying to find product-market fit.

- Test your hypothesis

- Launch fast

- Do things that don't scale

Finding Your First Users

There's no silver bullet for user acquisition.

You've got no idea what the pain points of customers really are. You've never sold that before. You don't have any success stories to point to, or testimonials. Those first users are always going to be the hardest.

And so it's your responsibility as a founder to do whatever it takes to bring in your first users.

Don't focus on ROI, focus on growth. Those first two users are going to take a lot of handholding, a lot of personal love, and that's okay - that's essential for building a company

Don't giving your product for free. In general, cutting costs or giving the product away is an unsustainable strategy. You need to make sure that users value your product. And you know, people treat products that are free in a much different way than a paid product.

Turning Those Users Into Champion

A champion is a user who talks about and advocates for your product. Every company with a great growth strategy has users who are champions. The easiest way to turn a user into a champion is to the delight them with an experience they are going to remember, so something that's unusual or out of the ordinary – an exceptional experience.

Just talk to those users, spend a large chunk of your time talking to users. You should do it constantly, every single day, and as long as possible. In the early days, the product and the feature set you launch with is almost certainly not going to be the feature set that you scale with. So the quicker you talk to users and learn what they actually need, the faster you can get to that point.

- Run customer service yourself: there's going to be an instinct to quickly pass off, and that's because it's painful.

- Proactively reach out to current and churn customers: when a user actually leaves your service, you want to reach out and find out why, both because that personal outreach can make the difference between leaving and staying; sometimes people just need to know that you care and it's going to get better. And even if you can't bring them back, there's a chance that you can learn from the mistakes you made that caused them leave, and fix it so you don't churn users out in the future in the same way.

- Social media and communities: You need to know how people are talking about your brand. You need to try to make sure that when somebody does have a bad experience, and they're talking about it, that you make it right.

Problems are inevitable: You're not going to have the perfect product; things are going to break; things are going to go wrong. That's not important. What's important is to always make it right, to always go the extra mile and make that customer happy. One detractor who's had a terrible experience in your platform is enough to reverse the progress of 10 champions. That's all it takes, is one to say, "No you shouldn't use those guys for X reasons," to ruin a ton of momentum.

Finding Your Product Market Fit

And as engineers your instinct is building a platform that's beautiful, clean-code, and that scales. You don't want to write a duct tape code that's going to pile on technical debt. But you need to optimize for speed over scalability and clean code

A great rule of thumb is to only worry about the next order of magnitude, so when you have your tenth user, you shouldn't be wondering how you are going to serve one million users. You should be worried about how you're going to get to 100. When you're at 100, you should think about 1,000

Necessity is the mother of invention: you'll find a way to make it work, you will survive. Those bumps are just speed-bumps, and speed is so so important early.

Do things that don't scale as long as you possibly can. There's not some magical moment; it's not Series A, or it's not when you hit a certain revenue milestone that you stop doing things that don't scale. This is one of your biggest advantages as a company, and the moment you give it up, you're giving your competitors that are smaller and can still do these things, that advantage over you.

Press

Press should have targeted audience and goals, e.g. investors, customers, industry.

What is a story? e.g. product launches, fundraising, milestones/metrics, business overviews, stunts, hiring announcements, contributed articles.

Think about your story objectively, you don't have to be original, just original enough.

Mechanics of a story:

- think of a story

- get introduced

- set a date (4-7 days in advance)

- reach out

- pitch

- followup

- launch your news

Getting press is work, make sure it's worth it, getting press doesn't mean you are successful, press is not a scalable user acquisition strategy.

If you decide press is worth it, keep contacts fresh, regular heartbeat of news, golden rule "pay it forward": you should help your fellow entrepreneurs get coverage because they'll help you get coverage.

Lecture 9 - How to Raise Money (Marc Andreessen, Ron Conway, Parker Conrad)

How to decide to invest?

So what makes us invest in a company is based on a whole bunch of characteristics. To invest in 700 companies that means we have physically talked to thousands of entrepreneurs and there is a whole bunch of things that just go through my head when I meet an entrepreneur.

Literally while you are talking to me in the first minute I am saying “Is this person a leader?” “Is this person rightful, focused, and obsessed by the product?” I am hoping—because usually the first question I ask is "What inspired you to create this product?"—I’m hoping that it’s based on a personal problem that that founder had and this product is the solution to that personal problem.

Then I am looking for communication skills, because if you are going to be a leader and hire a team, assuming your product is successful, you have to be a really good communicator and you have to be a born leader. Now some of that you may have to learn those traits of leadership but you better take charge and be able to be a leader.

Extreme outliers

Venture capital business is 100% a game of outliers, it is extreme outliers. So the conventional statistics are in the order of 4000 venture fundable companies a year that want to raise venture capital. About 200 of those will get funded by what is considered a top tier VC. About 15 of those will, someday, get to a 100m dollar in revenue. And those 15, for that year, will generate something on the order of 97% of the returns for the entire category of venture capital in that year. So venture capital is such an extreme feast or famine business. You are either in one of the 15 or you’re not. Or you are in one of the 200, or you are not. And so the big thing that we're looking for, no matter which sort of particular criteria we talked about, they all have the characteristics that you are looking for the extreme outlier.

Invest in strength versus lack of weakness. And at first that is obvious, but it’s actually fairly subtle. Which is sort of the default way to do venture capital is to check boxes. So really good founder, really good idea, really good products, really good initial customers. Check, check, check, check. Okay this is reasonable, I’ll put money in it. What you find with those sort of checkbox deals, and they get done all the time, but what you find is that they often don’t have something that really makes them really remarkable and special. They don’t have an extreme strength that makes them an outlier.

On the other side of that, the companies that have the really extreme strengths often have serious flaws. So one of the cautionary lessons of venture capital is, if you don’t invest in the bases with serious flaws, you don't invest in most of the big winners. And we can go through example after example after example of that. But that would have ruled out almost all the big winners over time. So what we aspire to do is to invest in the startups that have a really extreme strength. Along an important dimension, that we would be willing to tolerate certain weaknesses.

What VC looks for in a company

When you first meet an investor, you’ve got to be able to say in one compelling sentence that you should practice like crazy, what your product does so that the investor that you are talking to can immediately picture the product in their own mind.

You have to be decisive, the only way to make progress is to make decisions. Procrastination is the devil in startups. So no matter what you do you got to keep that ship moving. If it's decisions to hire, decisions to fire, you got to make those quickly. All about building a great team. Once you have a great product then it’s all about execution and building a great team.

There might be a path to kind of, there’s enough cash flow it seemed compelling enough that I could do that. It turns out that those are exactly the kinds of businesses that investors love to invest in and it made it incredibly easy. Bootstrap for as long as you can. “Well, when are you going to raise money?” "I might not," and I go, "That is awesome." Never forget the bootstrap.

The key to success is be so good they can't ignore you. You are almost always better off making your business better than you are making your pitch better.

Raising venture capital is the easiest thing a startup founder is ever going to do. As compared to recruiting engineers, recruiting engineer number twenty. It’s far harder than raising venture capital. Selling to large enterprise is harder, getting viral growth going on a consumer business is harder, getting advertising revenue is harder. Almost everything you'll ever do is harder than raising venture capital

It’s often said that raising money is not actually a success, it's not actually a milestone for a company and I think that is true. And I think that is the underlying reason, it puts you in a position to do all the other harder things.

Relationship between risks and cash

Relationship between risk and raising cash, and then the relationship between risk and spending cash.

- founding team risks, are the founders going to be able to work together.

- product risk, can you build the product.

- technical risk, maybe you need a machine learning breakthrough or something. Are you going to have something to make it work, or are you going to be able to do that?

- launch risk, will the launch go well.

- market acceptance risk, you will have revenue risk.

- sales force, is that can you actually sell the product for enough money to actually pay for the cost of sales?

- cost of sales risk.

- viral growth risk.

So a startup at the very beginning is just this long list of risks, right, and the way I always think about running a startup is also how I think about raising money. Which is a process of peeling away layers of risk as you go. So you raise seed money in order to peel away the first 2 or 3 risks, the founding team risk, the product risk, maybe the initial watch risk. You raise the A round to peel away the next level of product risk, maybe you peel away some of the recruiting risk because you get your full engineering team built. Maybe you peel away some of your customer risk because you get your first five customers. So basically the way to think about it is, you are peeling away risk as you go, you are peeling away your risk by achieving milestones. And as you achieve milestones, you are both making progress in your business and you are justifying raising more capital.

Go through this because it is a systematic way to think about how the money gets raised and deployed. As compared so much of what's happening these days which is “Oh my god, let me raise as much money as I can, let me go build the fancy offices, let me go hire as many people as I can.” And just kind of hope for the best.

Don't ask people to sign an NDA. We rarely get asked any more because most founders have figured out that if you ask someone for a NDA at the front end of the relationship you are basically saying, I don't trust you. So the relationship between investors and founders involves lots of trust. The biggest mistake I see by far is not getting things in writing. When somebody makes the commitment to you, you type an email to them that confirms what they just said to you. Because a lot of investors have very short memories and they forget that they were going to finance you, that they were going to finance or they forget what the valuation was, that they were going to find a co-investor. You can get rid of all that controversy just by putting it in writing and when they try and get out of it you just resend the email and say excuse me. And hopefully they have replied to that email anyways so get it in writing. In meetings take notes and follow up on what’s important.

Process

- vote on great short executive summary

- phone call

- meeting

- background checks, back door background checks, get a good feeling about the company & market & commitment to invest

The most important thing at the seed stage is picking the right seed investors because they are going to lay the foundation for future fundraising events. They’re going to make the right introductions, there is an enormous difference in the quality of an introduction. So if you can get a really good introduction from an someone that the venture capitalist really trusts and respects, the likelihood that that is going to go well is so much higher than a lukewarm introduction from someone they don't know as well.

Maximum dilution

It seems like they are particularly rough for a Series A. You are probably going to sell somewhere between 20-30% of the company. Seed stage from what I have heard, it seems 10-15%.

It is important for the founder to say to themselves in the beginning "at what point does my ownership start to demotivate me?" Because if there is a 40% dilution in an Angel round, I have actually said to the founder "do you realize you have already doomed yourself?" You are going to own less than 5% of this company if you are a normal company. And so these guidelines are important. The 10-15% is because if you keep giving away more than that there is not enough left for you and the team. You are the ones doing all the work.

Finding phenomenal co-founders